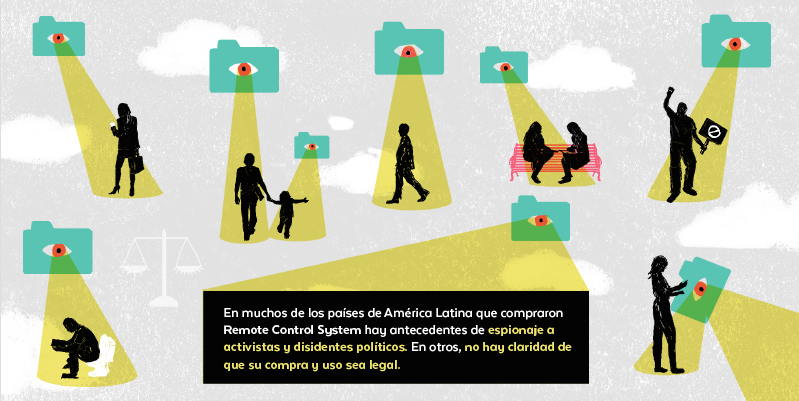

Digital surveillance is one of the main interests for governments in Latin America. A recent report launched by Derechos Digitales reveals that the vast majority of the countries within the region were involved with Hacking Team, the Italian company that sells a surveillance malware named Remote Control System (RCS) to public officials around the globe.

Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Honduras, Mexico and Panama bought licences for the use of Galileo or DaVinci, the commercial names for RCS. Argentina, Guatemala, Paraguay, Perú, Uruguay and Venezuela contacted the company and negotiated prices, but did not complete the sale.

Because of international limitations in the Wassenaar Arrangement, all negotiations and sales were made through intermediary companies. The most prominent intermediaries in the region were Robotec in Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama; and NICE Systems in Colombia, Honduras and Guatemala.

All of this information was kept secret until on July 5th of 2015, the company was hacked and 400GB of their information, including emails, contracts, invoices and other internal documents, were made public.

RCS is a software capable of gaining access to any type of information contained in a computer or cell phone: passwords, messages and emails, contacts, calls, microphone and camera, information from Skype or any message platform, geographic location, hard drive, every single letter from the keyboard, mouse clicks, screenshots and internet history. In other words: everything pertaining our digital private life.

The report by Derechos Digitales takes into account press articles that were published in the region after the hack, and provides a legal analysis of communication surveillance rules in the countries whose authorities contacted the company. The main conclusion is that the use of Hacking Team’s software does not comply with existing legal standards in the region, and therefore unduly infringes upon the rights to privacy, free speech and due process. Given the close relationship of Latin American governments with authoritarianism and undemocratic governments, the use of these tools is especially alarming.

For instance, in Ecuador, the technology made available by Hacking Team was allegedly used to spy on an opponent to the government of Rafael Correa. In Mexico, a country that is going through a severe human rights crisis, eight of the ten authorities than bought licences for RCS are not constitutionally authorised to use it. The Mexican intelligence agency(CISEN) requested 2,074 judicial orders to use the software, but there is no evidence that their use is justified.

The leaked information also revealed that the United States Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) was allegedly intercepting the traffic and communications from all Colombian citizens. It is also suspected that these type of tools might have been used against Vicky Davila, a journalist that investigates a male prostitution network within the police.

In Panama, the former president Ricardo Martinelli was personally involved in the negotiations with Hacking Team. In Chile, the Investigations Police said in an official statement that this kind of surveillance was made according to strict legal standards and with judicial authorization in each case. Nonetheless, court orders are not sufficient regarding RCS, and cannot guarantee their legitimate use due to its invasive nature.

From a legal standpoint, this type of software is not explicitly regulated in Latin America. Countries like Chile, Mexico and Colombia have broad dispositions regarding surveillance and equipment intervention, but with vague and imprecise language. The absence of clear regulation presents a problem because it opens the way for corrupt and arbitrary decisions on the use of hacking tools like RCS.

Even if the interception of communications is subject to judicial authorisation in Latin-American countries, this is not sufficient because Hacking Team’s software is much more invasive than a mere interception, as it can take over a device and thus have access to documents, peripherals, hard drive, and more. It is highly dubious that court orders could legally cover the use of these tools. Thus, due process concerns are raised.

It is worth noting that penal law sanctions illegal interception or intervention of devices in almost every analysed country. Nonetheless, only Panama has opened investigations on the matter.

Illegitimate surveillance is a problem that goes beyond Hacking Team: it implies a global market that abuses technology used by governments around the world, and which takes advantage of legal loopholes and poor mechanisms for transparency and accountability. A more open discussion around the standards that regulate this type of malware is necessary. High standards of transparency in the acquisition of these tools must be respected, and legal sanctions should be applied where required.

Ecuador

Ecuador Consentimiento libre e informado

Consentimiento libre e informado Innovación, Tecnología y Feminismo

Innovación, Tecnología y Feminismo